Deaf History Month runs from March 13th through April 15th, commemorating the contributions the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community has made to US society and culture. In honor of Deaf History Month, CyraCom is republishing some of our most popular blog posts on deaf-related topics, including this one from 2015 on the history of Deaf education in America:

Today, American Sign Language, or ASL, is the most famous and well-recognized method of communication for the Deaf community in this country. You may be surprised to know that there was a time in our history when ASL was thought to do more harm than good, to the point where teaching it was banned from most schools for decades.

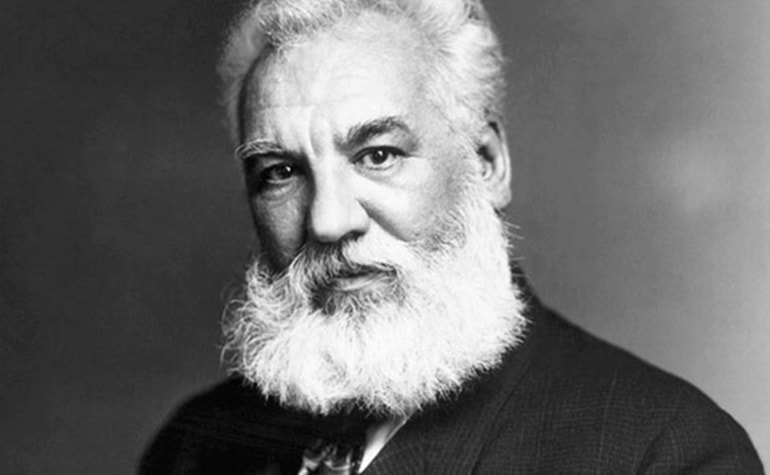

During the time it was banned, ASL s most famous critic was none other than inventor Alexander Graham Bell. Bell s mother, Eliza Bell, was Deaf. His father, Melville Bell, created a program called visible speech, which used symbols to teach people how to speak languages they had never heard. Bell began working with his father in the 1840s, teaching visible speech at various schools for the deaf. By the 1870s, visible speech had progressed to Oralism, the teaching of deaf individuals by only using the spoken word, and the idea was beginning to gain momentum. At this point, Bell began to advocate and lecture on the benefits of using the spoken word instead of ASL to educate Deaf individuals.

As he grew in wealth and fame for his inventions, so too did Bell s promotion of Oral Education as the superior educational option for the Deaf. He traveled extensively throughout the United States and Europe, speaking about the benefits of Oralism over ASL. He would appeal to the parents of deaf children, telling them that the only way that their children would ever be part of society was to learn how to speak. Because of Bell’s fame and wealth, society’s elite politicians, doctors, and educators took notice. The campaign against ASL in the United States had begun.

In 1880, this struggle culminated in an event known as the Congress of Milan. Deaf educators from all over the world gathered in Italy to discuss methods for educating Deaf individuals. Those who supported Oralism were allocated almost three days to present; the supporters of ASL, in contrast, were given three hours. At the end of the conference, attendees voted to ban sign language as a primary means of educating deaf individuals, deciding instead that Oralism was the superior method. This was the beginning of period where deaf children were not allowed to use Sign Language to learn or communicate. From then on, the Deaf only used and taught American Sign Language in secret.

This view of ASL, though ultimately misguided, persisted for 100 years. The tide began to turn in 1960, when the linguist William Stokoe published Sign Language Structure. Stokoe s research offered compelling evidence that sign language shares the essential characteristics of a spoken language, and he argued that it should be considered equivalent to, and afforded the same respect as, other languages.

Further progress was made at the 15th International Congress on the Education of the Deaf (ICED) in 1980, where delegates modified the findings of the Congress of Milan, and declared that all deaf children have the right to flexible communication in the mode or combination of modes which best meets their individual needs. Finally, in 2010, the 21st ICED held a formal vote to do what the 15th had not: they rejected all of the 1880 Milan resolutions, leaving the Deaf community free to be educated in their method, or methods, of choice.

Now that you know a bit more about the history of Deaf education, download our whitepaper for tips on treating Deaf patients in a healthcare setting.